A spectre is haunting Europe–the spectre of authoritarianism.

Is it fair to rewrite the first sentence of Marx-Engels manifesto in this manner?

As we observe the worrisome process of ‘Erdoğan vs Germany’, now having developed into ‘Erdoğan vs Netherlands’, it is inevitable how enthusiastically his relentless drift to test the intolerance vis a vis democratic tolerance is received by the far-right in Europe in general.

Authoritarian leaders have been known to to thrive over the conditions that the democratic tolerance provides. Their journey towards their ‘final destination’ defies checkpoints; their very ‘free ride’ aims to gobble up all legitimacy – by way of subversion of the rules and regulations otherwise widely agreed.

What we have been witnessing – with the rise of Putin, Erdoğan and Trump -, mind you, is only a harbinger of what we will see in the future; only more and more of it. Unless, of course, Western Europe has a strong enough memory, and practical means, to fend the spectre off.

But it does.

Every day that passes with what takes place in trauma-stricken Turkey comes as a confirmation of how Hitler enhanced his power to the point of no return – almost as a playbook. Accumulation of anger over historic treaties; reproduction of the illusions of grandeur, the constant invention of domestic and foreign enemies – all accompanied by lies. In many ways Erdoğan represents a reincarnation of the ‘supreme leader’ that is only possible with the permissions that make it possible.

But there is a big difference of then and now.

Some 80 years ago, Europe was caught unprepared mostly because of its lack of legal consensus – through international legal institutions – that would make life very difficult for ‘dictator wanna-be’s. Today, the main difference is just that: legal ground is stronger and its is high time democracies should exhaust all their possibilities to marginalise evil that threatens their existence.

Erdoğan is in constant need for enemies – to keep his power base intact. He needs polarisation as a springboard for making it absolute, eternal. But, unlike Hitler, his invented enemies do not last long.

They are temporary, and slippery; they are either as cunning as his rule, or more powerful; and this very fact threatens his ambitions. His ‘enmity experiment’ with Syria has come to a bitter end with the latest developments; his arm-wrestling with Putin proved costly, showing that when thuggery meets thuggery all turn into a high-risk gamble.

The attempts to declare Lausanne Treaty as outdated backlashed, as the efforts to create a crisis in the Aegean with Greece – according to latest confirmed reports from Greek press – appears to have led to a clear ‘stop that!’ from Trump Administration. And, as we see, testing Germany’s patience by stretching the slander beyond all moral limits – comparisons to Nazism – doesn’t really seem to be promising for his purposes for maintaining popularity at home, in the long run.

History has taught us another lesson: If a power-grabber runs out of his political arsenal of confrontations, turn to the weak and vulnerable, more and more. So, if Erdoğan ends up empty-handed with how intends to instrumentalize Germany for his dreams as a single ruler of Turkey, that’s what he will do . Germany was seen as a useful punch-bag for a victory in the referendum, and indeed, if he wins, Turkey will be entirely redefined in the eyes of the West and its institutions.

If Turkey rejects the constitutional amendments in April 16 or, if by an unexpected act of panic the vote is cancelled before that, take it for granted that Erdoğan will do his best not to lift the state of emergency. It will have overlapped with the continued marginalisation in Syria and, if so, he will have to geometrically increase the oppression over the Kurds in Turkey in particular – perhaps, as some fierce critics say, hoping for an uprising which may give him a nationalist lead role.

Against that horrifying perspective, the current picture in Turkey leaves us about what to do to push back this geostrategically disastrous trend. Neither apathy, nor aggressive political escalation prove useful.

The EU has for far too long ignored Turkey. It has never been honest; it temporized with the hopes of Turks and Kurds. Jerking around with that society was like playing with fire, simply because it was at unease in the midst of problems whose solutions were long overdue; and it was known that a clear perspective of membership, however far ahead, was the medicine. Sadly, that momentum is lost, gone forever. Turkey has taken a sharp right turn, doomed to produce (and export) hostility and qualm.

Erdoğan plays just on this. He will not give up on either having his own anti-democratic values be acknowledged in the EU, or expecting that a decision to terminate the negotiations will come from there. Keeping this prospect on razor’s edge also serves his purposes.

Have we run out of resources to deal with the spectre? As I believe, we have the legal base; and we need a full engagement from the good forces of the EU to exhaust all the possibilities. It is the European Court of Human Rights (ECtHR) which is nowadays feeling the heat, after a period of hesitation. Yes, its relations with Turkey due to the breaches have always been troubled; but the way things have reached the breaking point since the failed coup in July last year requires that ECtHR is facing a historic test of make or break with Turkey’s commitment to the western norms. The Court’s hesitation to take over the cases until recently was because it had believed that Turkish Constitutional Court (AYM) would be responsive to the complaints from the dissidents and journalists imprisoned for months without even being able to meet their lawyers properly.

But AYM, apparently eclipsed by Erdoğan’s rage, remained silent.

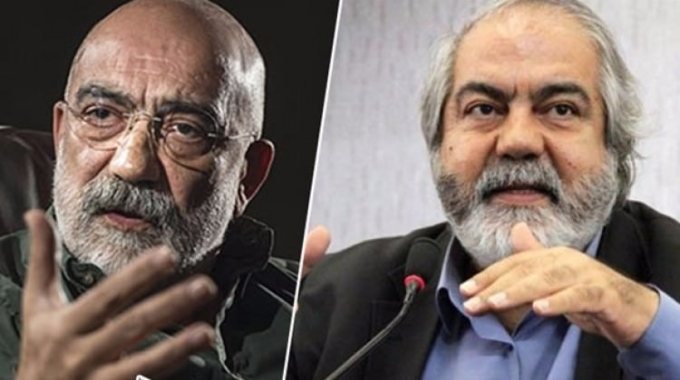

So, most recently ECtHR accepted to deal with two spectacular cases without any further delay and this came as good news. The first one was an application by the novelist and former editor in chief (of Taraf newspaper) Ahmet Altan and his academician brother Mehmet Altan; and the second was the case of Şahin Alpay, a columnist and one of the frontline figures of liberalism in Turkey. Both cases are of the same essence: these ‘suspects’, held in jail for months, say the accusations are based on what they expressed as pure opinion, thus groundless; and they are being held unlawfully as prisoners. These are the two pilot cases of post-coup Turkey – which among many others also will be about the case of Deniz Yücel – and the way they are handled will shed a lot of light on how Erdoğan’s government will respond. This time with a difference: the legal judgment over the massive oppression in a partner country ‘negotiating’ with the EU will have to define its true path, also affecting its relations with the western institutions altogether.

Erdoğan hopes that, given the apathy in the Council of Europe about Azerbaijan and Russia, it may be ‘business as usual’, but he will have to be remembered that Turkey is far more special than any other country.

This crucial legal battle requires a full-scale engagement from the bar associations from all corners of the EU. Erdoğan’s government will have to be told that this is not the Europe of 1930’s.

One can only hope that much.