Polls analysing the key contenders to take the French presidency suggest voters have fixed their intentions on candidates from the right and centre-right. Yet, in a climate of limited confidence in pollsters, it is worth recognising that parties of the Left in France are now starting to play their hand.

Yesterday, breakaway former Economy Minister Emmanuel Macron announced his presidency bid, a move that may well drive some voters away from the current centre-right frontrunner, Alain Juppé. Incumbent President François Hollande is expected to announce next month whether he will run, although record low approval ratingsdemonstrate how slim his chances are. Meanwhile, Prime Minister Manuel Valls has also been put forward as a contender, but his formal declaration will likely depend on Hollande’s decision.

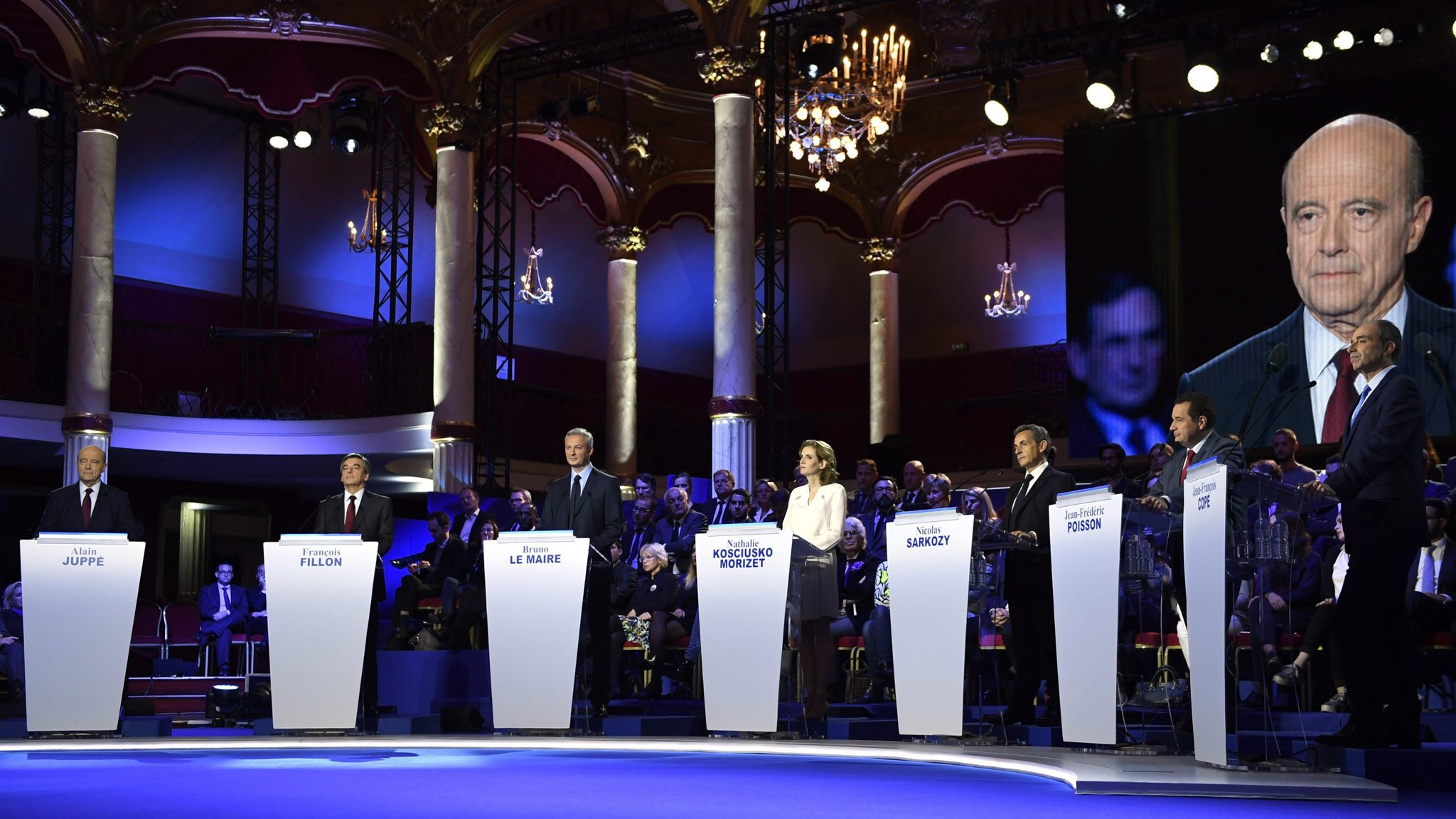

Still, with the first round of centre-right primaries approaching this Sunday (with the following round scheduled for 27 November), there is good reason to focus attention on the leading candidates for nomination: former President Nicolas Sarkozy, Mayor of Bordeaux Alain Juppé, and former Prime Minister François Fillon (according to a new poll). A closer look at their positions on Brexit might shed some light on what the UK should expect from a new French partner.

Centre-right hopeful: Nicolas Sarkozy

Sarkozy made it clear that following the UK vote, the Le Touquet border agreement [according to which the British border force carries out immigration controls at Calais] must be up for renegotiation in order to address the migration crisis in France. Advocating for UK “hotspotting” to process those asylum seekers set on reaching the UK, he said,

Britain should decide freely…whether they intend to keep [these migrants]. It is not up to us. We should therefore open a hotspot in England…The British cannot say ‘we refuse Europe because it is too inconvenient, but when there is a benefit [to us], we want to keep it’.

In an opinion piece for the Financial Times today, he adds,

Nobody can be in and out at the same time, or enjoy privileges without fulfilling responsibilities. This has absolutely nothing to do with retribution: it is simple logic. No European government could agree to grant the UK free access to the single market if Britain does not accept rules, duties and concessions, including the free movement of Europeans, in return.

Sarkozy also suggested that Europe “could not continue to function in its current form” following Britain’s vote to leave. He has called for a new treaty, founded on five key pillars: Schengen reform, the creation of a new European economic government, proper application of subsidiarity, the restriction of Commission competences, and an end to further enlargement. He has also proposed allowing Britain to vote again on EU membership on the basis of this new treaty:

[I will say,] we have a new treaty on the table so you have the opportunity to vote again…Do you want to stay? If you do, that’s great…If it’s a ‘no,’ then it’s a real ‘no.’ You are either in or out.

However, there is no clear indication of what treaty provisions he believes would trigger a turnaround from the UK and any radical change of the EU is unlikely to materialise within the UK’s planned Article 50 timetable. Nevertheless, his desire to shake things up in the EU would certainly make a Sarkozy presidency unpredictable, and this includes with regard to Brexit.

Centre-right frontrunner: Alain Juppé

Juppé has echoed the current French President François Hollande in advocating for a hard and fast Brexit:

[The UK’s] exit should be rapid, and it shouldn’t be a question of renegotiating any form of complementary arrangement. The British cannot continue with both one foot out and one foot in.

However, in a later interview with the Financial Times, his tone was more conciliatory:

[Brexit] does not mean we are going to punish the UK, we need to find ways to cooperate, to find a solution to have the UK in the European market, one way or another.

He also hopes to maintain “very close bilateral cooperation” on military and defence issues. However, he offered little compromise on Le Touquet:

The logic requires that border controls take place on British soil…We must move the border back to where it belongs.

On European integration, Juppé seeks to reclaim France’s “historic responsibility” in driving the EU project, highlighting his plans to “redefine the boundaries of competences,” “relaunching the Eurozone” and “renegotiating” Schengen. However, unlike Sarkozy, he has dismissed the idea of drawing up a new treaty, calling it “an end-point, not a starting point.”

Up-and-coming: François Fillon

Despite having publicly confessed his “admiration” for Margaret Thatcher in the past and being married to a Welsh woman, Britain should not necessarily expect Fillon to take a soft negotiating stance. After the Brexit vote, he said,

This decision cannot lead to uncertainties that last years, things must be decided quickly, without being aggressive towards the UK, but without being complaisant either.

Fillon has also advocated for a reform of Le Touquet, declaring that Britain must “take back their borders.”

Understanding France’s political considerations

From France’s standpoint, Brexit concessions are unlikely to be a priority in the midst of upcoming presidential elections, continued migration concerns and a possible extension of the state of emergency, which was introduced last year following successive terrorist attacks. Indeed, adopting a harder line in the upcoming Brexit negotiations may even be viewed as part of the solution to some of these domestic concerns. So how much stock should Britain put in messages emanating from the centre-right frontrunners at this crucial juncture in French politics?

One theory often proposed is that a new French president will advocate for punitive exit arrangements in a bid to puncture the rise of the Front National at home. This is, however, unlikely to be a sensible long-term strategy: once the elections are over, the motivation to curb public support for Le Pen is unlikely to weigh as heavily. Such an argument also fails to recognise the Front National’s informal influence: much like UKIP, Le Pen need not be elected, nor have many parliamentary members, in order to shape the political agenda or the stance of other leaders.

Above all, it seems that in the absence of much else to say about Brexit so far, the French centre-right has narrowed in on the only concrete issue to hand – a desire to renegotiate the Le Touquet treaty. Certainly, there is a clear consensus from centre-right candidates that this is part of Britain accepting the consequences of its decision to leave the EU. While this could indeed be a politically messy flashpoint between the UK and the EU, it pales in comparison to the wider issues at the heart of Britain’s departure. As Juppé suggested, the future of defence and security cooperation is perhaps a more significant topic to address in upcoming negotiations, given Britain will remain France’s most reliable and credible European defence partner, irrespective of membership of the EU.

More generally, though, the reality is Brexit was far from the dominating topic in the recent campaign to win the centre-right presidential nomination. Based on what the hopefuls have said, we could expect Sarkozy to be an energetic but unpredictable negotiator (the benefits and disadvantages of which remain unclear), while Juppé presents himself as a more pragmatic and rational player. Fillon’s rise may be unexpected, but his strong liberal stance could present opportunities for Britain on trading relations.

However, a large degree of uncertainty remains, and it would be no use hiding that France will likely be among the toughest around the negotiating table.

*This article originally appeared on Open Europe.