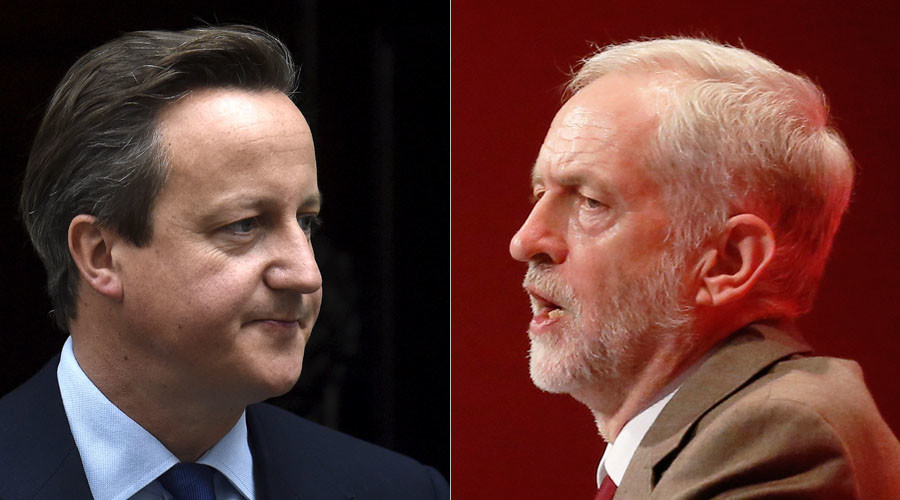

David Cameron could be forgiven if he enters the Tory Conference week thinking about his place in history. This, after all, is a man who doesn’t have to win another election, since he’s given himself a final term firewall against any future electoral catastrophes. Not only that, but he’s been able to witness Jeremy Corbyn’s utter catastrophe of a party conference over the past week.

Mr. Corbyn is a delight in many ways. He’s not quite as different as a party leader as some hopefuls are suggesting , admittedly. George Lansbury and Michael Foot were also bizarre left-wing true-believers with a lofty disdain for practical politics, and both proved electorally disastrous for the Labour party, albeit from a better intellectual vantage point than the fuzzy minded Corbyn. But Corbyn is the first of that mould to appear in the age of constant media, and his disdain for the “media commentariat”, coupled with his notoriously badly structured, dull black holes of speeches have all gone to contribute to the carefully spun image of a man who is “authentic”.

Corbyn’s conference must have been a sheer joy for David Cameron. The Labour leader’s select-a-policy style, and his refusal – or inability – to have his shadow cabinet speaking from anything like a single song-sheet, must all be making the current leasee of No. 10 Downing Street giddy with the prospects of his future greatness. And Cameron has to think about his future greatness as he has no more general elections to win.

What he does have, though, is a referendum to win and if he is to finally rest on the front bench of Great Tory Leaders he will need to ensure that he persuades the country – and much of his own party – to stay in Europe. Whatever the Euro-sceptics say, Cameron doesn’t see leaving Europe as much of a triumph for his avowedly internationalist approach.

Musing on possible future greatness might have led Mr. Cameron to read more carefully the obituaries of former Labour cabinet minister Denis Healey this weekend. Whether great or not – there is plenty of scope for debate – Healey was one of the best known politicians of his era. He was an early example of the “celebrity” politician who could probably be readily recognised by the average voter in the street. Bushy eyebrows may have helped, and the fact that he was thus easily caricatured by the greatest performing impressionist of his day, Mike Yarwood, but Healey was also well known because he was trenchant. He rarely expressed modest views and wasn’t shy about condemning his opponents. His reference to Geoffrey Howe having all the savagery of a dead sheep in his parliamentary attacks has been well recorded. Less often noted, and more scathing, was his outraged condemnation of Margaret Thatcher as a prime minister who “gloried in slaughter” during the Falklands War.

The problem for Denis Healey – who has received universally positive obituaries – is that his greatest achievement was born out of disaster. As Labour Chancellor of the Exchequer during the awful 1970s he had to advise a recalcitrant party that the days of ambitious spending were over. He began – in the teeth of massive Labour opposition – a sharp programme of austerity. It was forced upon him by the fact that he was the first – and to date the only – Chancellor to ask for a loan from the IMF to tide the tanking British economy over. Greece’s Prime Minister might be particularly interested in Denis Healey’s career at the moment.

I doubt that, when he entered politics after a heroic military career during World War II, Healey envisaged his claim to greatness resting on such a terrible reversal of fortunes. He spent the rest of his active political career trying to persuade the Labour left-wing of the need for responsible policies and to appeal to centrist voters. He failed in this.

Mr. Cameron could be forgiven if he wasn’t at least half wondering whether the lesson of Denis Healey’s ‘greatness’ would be that a possible failure to keep Britain in Europe might, after many years, be viewed as an heroic last stand. But even if his musings do go in that direction, it’s clear that it is not the narrative he wants. A referendum may be two years away, but this week’s Conservative Conference may help to show us in which way David Cameron’s future reputation will lie.